Acceleration Policy: Four easy pieces

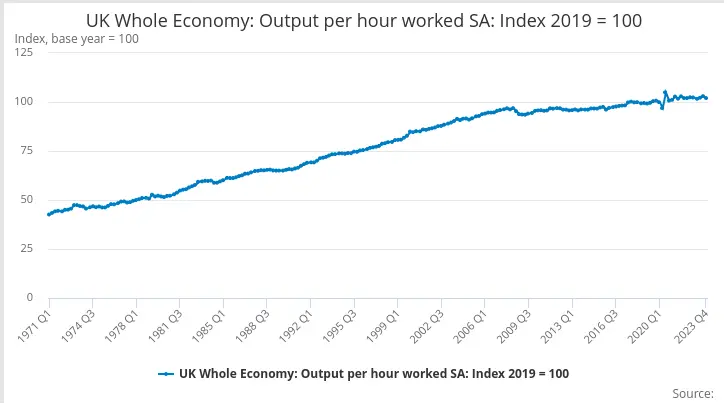

📍 Silicon Fen, EnglandSince 2008, Britain has averaged a measly 0.8% yearly productivity growth, being outstripped by productivity gains in the United States and in the Eurozone. This has created a lost generation of workers who have seen their living standards eroded owing to their earnings not keeping pace with their living costs.

(Source: ONS, UK Whole Economy: Output per hour worked)

As of writing, there is a net outflow of young Britons seeking work overseas. It is expensive to be young now. Housing in areas with solid employment of all sorts is now ruinously expensive. What would have been a home for an ordinary working man in the Petersfield area of Cambridge is now even too expensive for a young professional in a well-earning job, and even these jobs aren't that well-compensated relative to equivalent jobs in America and the Antipodes.

Our young and talented are leaving in their thousands.

Decline is not inevitable, and decay is never irreversible.

Summary

- Ban non-compete clauses in employment contracts.

- Allow councils to compete with each other for remote work liquidity.

- Use the state's purchasing power to subject market bottlenecks to market forces.

- Free up the land with planning reform and a land value tax.

Banning non-compete clauses

I have experienced restrictive covenants in employment contracts. They are a stain on the tech industry. The notion that an employer can dictate who you can or cannot work for after they have stopped paying you is an anachronism that should have been left in 1531.

Sure, it is possible to challenge these clauses, but that option is expensive, and most employees wouldn't be able to do this owing to financial constraints. I've seen some complete honkers of restrictive covenants before, and my inclination is that business has abused them and pushed them well past the scope for which they were originally intended.

A ban on non-compete clauses would achieve the following:

-

It would give more bargaining power to the employee. This is a good thing. The tech industry has gone to fantastic pains to essentially homogenise employees to the degree that most places use the same technology stack with the same cloud services, even using the same linting rules and code standards. This has been a boon to the tech businesses in that they can chop and change employees however they please. Why shouldn't this work both ways?

-

It would encourage a diversification of skillset in business. This is also a good thing. It would force businesses to plan ahead. Too many businesses are centralised on one particular engineer, for whom the bus factor is very high indeed. Without being able to impose a restrictive covenant on this sole engineer, the employer would have to ensure there is no single engineer with the keys to the kingdom.

-

It would unlock startups. At the moment, if an engineer has a good idea or a prototype that was rejected by management, they might be unable to commercialise it on their own account because that would fall under a non-compete clause. The threat of legal action enough to make most investors run to the hills, a net negative to the business ecosystem.

The usual arguments against non-compete clauses revolve around businesses being unwilling to invest in employees if they can't guarantee that the employee just won't clear off after six months. I argue that this is poor business practice in the first instance. Why should the state be expected to shield this practice? If the business doesn't want to invest in an employee, I bluntly suggest that they don't. Enterprise has its risks.

It is worth pointing out that the American state of California bans non-compete clauses, and California's Silicon Valley remains the centre of the world's technology industry. Non-compete clauses, originally designed to prevent salesmen from stealing client lists (which could be covered by a non-disclosure in any case), belong in the dustbin of history.

Paying remote workers to relocate

This is a spicy opinion that once made a local councillor hop up and down, incandescent with rage. It's bad enough in his eyes that people can just work from home, making his investments in Silicon Fen office buildings worth less. Why should King's Lynn and West Norfolk District Council pay for someone to work from home?

My answer is very simple: it's a value siphon. Someone who commutes from Downham Market to Cambridge generates a lot of value in Cambridge. They can pay for an overpriced latte from one of Cambridge's many bougie coffee joints during a lunch break. They might pick up a newspaper from Cambridge train station. This money stays in Cambridge, but how about an opportunity for King's Lynn and West Norfolk District Council to siphon some of that money away?

A simple scheme would work like this: encourage remote workers to move to a town, they get a council tax rebate-- but if they move before five years or so, they have to pay it back.

If they do this and get enough young-ish remote workers, the town ends up siphoning the following from the city:

-

Value from ancillary services: my experience is that you never lose the taste for bougie coffee, so I go to the new bougie coffee joint in town. This applies to other services too. Some services cannot be offered over the internet.

-

Talent. Young talent with an appetite gathering in the same places allows for a cross-pollination of ideas. A few might even start businesses! For a bonus, start a co-working place which doesn't have to make a profit, just enough to keep the lights on, and offer start-up services from there.

I note that this might go some way to address regional imbalances, and doesn't require the council cadging "levelling-up" funds from central government, affording the council some more leeway in how it runs such a programme.

Using demand-side policies to address component bottlenecks

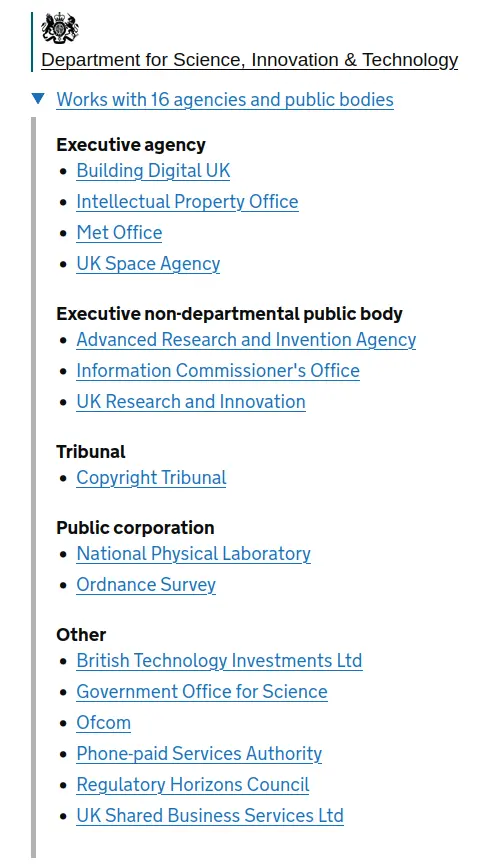

In Britain, we have a department of government called the Department for Science, Innovation, and Technology. That department works with sixteen agencies and public bodies.

Notice anything about these agencies and public bodies? They're another step removed from researchers and industry. It's another layer between incentive provision and incentive use.

This doesn't solve the cost issue of innovative products. It merely allows more people to buy them, but the subsidy is an anti-incentive to reducing costs, because when the cost drops below a certain amount, the state will turn the tap off. What's needed is a way to identify a particular bottleneck in why a product deemed beneficial is prohibitively expensive relative to its use and make that component dirt cheap.

Why not do what the Americans did in the 1950s? They stoked demand for semiconductors by telling Silicon Valley that they would buy a quantity of whatever they made at fixed price X for Y years. This created the demand. It also created an incentive for the semiconductor manufacturers to mass produce their chips in a generic way such that people other than the defence industry could use them. If they're able to produce below price X, they can make profit. And whatever the defence business didn't use, they could sell to consumer electronics manufacturers.

Ten years after that, Intel came along with the 8080 chip, and the rest is history.

Find something that is a net benefit to society (but expensive), find the cost bottleneck, provide the financial incentive to mass produce enough of these bottlenecks to drastically reduce its component price, and let the markets cook.

Freeing up the land

The biggest portion of the cost of building a house is the land. Land with outline planning permission commands a premium. This has been the case for many years, but between the supply of land with this planning permission being constrained either through geography or through market distortion and the cost of construction creeping upwards, house prices today relative to a worker's output are the highest they've ever been.

Even a humble three-bed house with a garden in the part of Cambridgeshire where I'm from requires the equivalent of seven times the median salary, and this is a house intended for an ordinary working man and his family. What is the bottleneck here?

I don't think it's material costs. There are companies out there which can build a flat-pack house. They're not glorified rabbit hutches either: built with cutting edge materials, they hold heat better in the winter, cool easier in the summer, and parts are interchangeable at a claimed 25% cheaper than a regular house.

I don't think it's personnel either. It is easy for a foreign worker to move to Britain, gain a few qualifications (or not even that), and enter the construction trade under a Skilled Work Visa. Even then, we have plenty of brickies and tradies in this country. They're never short of work.

My inclination is that it's to do with the land and the permissioning of land. It's a poorly kept secret that many homebuilders buy up tranches of land and sit on them, often for decades. This is a luxury only available to homebuilders, because they can afford for outline planning to lapse. During that time, it isn't used for much at all. Much of this land isn't suitable for agriculture and if it's brown belt land, it's unsuitable for dwelling or even parking your car on.

A simple way to deter this practice is a Georgist Land Value Tax. It's very easy to assess and very difficult to duck. No property ownership transfer without settling the tax affairs. Even let the landowner assess the value themselves-- but afford the state the right to buy at that value.

There's also the planning permission question itself. The Town and Country Planning Act (1948) sought a greater balance between the wants of the landowner and the desires of the community, but it also gave the homeowning community every tool it ever needed to constrain the supply of housing in an area. Having sat in my fair share of planning meetings, I do not believe that "the community" has the training or the incentive to make informed planning decisions. The homeowning community, owning assets which have appreciated massively in the past fifty years, does not have the interests of the wider community at heart. Reducing the community's power to block inoffensive housing projects would correct this balance.

Allow councils and planning officers to create a style guide for an area, and require builders to keep to it. This style guide can be drafted as a community effort so democratic process can be preserved, but there should be no carve-outs and no special exceptions. What would apply to a single dwelling on a plot of land should apply to a hundred dwellings on an out-of-town brownfield site. The style guide should be simple enough for any builder to understand, and available to download complete with a version history.

All of these policy proposals would meet with substantial opposition, but I believe them to be worth any opprobrium.

This country can't continue in stagnation for many more years. It was made particularly clear in the most recent general election that when people are shut out of economic growth and shut out from buying into a particular mode of living, they won't think twice about rejecting the current settlement and pursuing altogether more radical proposals.

The choice is simple: either accept creative destruction or bear witness to the destruction of creation.